This World is Not My Home

Kentucky Route Zero was released act by act over the course of seven years, and when its story finally came to a close, it made clear one last time just how trapped its players were in the audience.

I

Trying to recommend Kentucky Route Zero to people who haven’t played it always leaves me feeling pretentious.

It can’t be helped. Try telling somebody that the game you want them to play is “video games’ answer to the great American novel” and you’ll generally be met with benign confusion. “It’s a little bit like Jack Kerouac and Gabriel Marquez collaborated on a playable theatre production,” I say, feeling like I failed some sort of critical speech check.

And yet, Kentucky Route Zero is, unmistakably, inescapably, essentially all of these things.

It’s a free-wheeling travelogue, the story of a ragtag troupe of loners and nobodies on a rambling odyssey over asphalt. It aches with the same loneliness as Kerouac’s On The Road, and it blurs the lines of reality and metaphor like Marquez’s magical realism.

Most of all, it is fundamentally and self-consciously a work of theatre. Better minds than mine have compared video games as a genre to a kind of participatory theatre in which we, the players, move the actors to their places so they may recite their lines and progress the narrative. I don’t think I have played a game that was as keenly aware of this facet of its own medium as Kentucky Route Zero, nor one that brings it to bear in such an affecting, isolating way.

Rather than leverage player participation to immerse or empower the player, as is so often the goal of video games, Kentucky Route Zero is sharp, even insistent, in its consignment of the player to the role of audience member.

It is a game determined to disempower you, to frustrate your attempts to influence the story and interact with its characters.

This is made most explicit in the lengthy intermission between Acts II and III, a section titled “The Entertainment.” In “The Entertainment,” you play the role of a barfly in a production of a stage play called… Barfly. You would be forgiven for thinking that, given your new titular status, this section might be where the game finally lets you in, lets you take some control.

You’d be dead wrong. Your character stays rooted in place while the play’s action happens around you. You can cast your gaze hither and thither around the theatre — at the audience, at the stage lights, at your fellow performers, at the critics in the wings, but you are not afforded so much as the chance to speak a single line of dialogue. You’ll read reviews of your own wordless performance as the play continues, all glowing commendations from the critics that surround the stage: “Perfectly cast,” they say! The sense that these reviews are barbs aimed through the screen at you, the player, is inescapable. The Barfly is mute, static, isolated, and completely incapable of influencing the events of the plot — who better to play the part than you, the player?

“The Entertainment” stretches on for 40 long minutes, the entire duration of which the game maroons you beneath the lights. If you want to see how it ends, you’ve just got to inhabit this narrative and let it roll over you.

This isolation, this inability to exercise control over the narrative, persists from Kentucky Route Zero’s first moments and never lifts, not even right at the game’s bitter end.

Kentucky Route Zero was released act by act over the course of seven years, and when its story finally came to a close, it made clear one last time just how trapped its players were in the audience. In Act V, you don’t directly control any of the characters whose stories you have been invested in — instead, you’re a cat. You meow and paw at those characters in the same way players meow and paw at the story, unable to influence it.

Kentucky Route Zero is not your story. This world is not your home.

There was a truth to be found in such lonely audienceship, hiding in the blurry boundary between the Barfly and I. Something honest and sincere lives in that alienation.

II

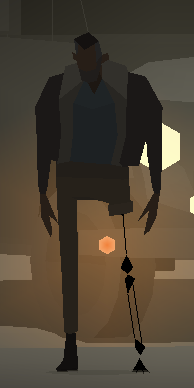

If Kentucky Route Zero could be said to have any primary character, the best candidate would be Conway, a recovering alcoholic, divorcé and delivery driver for Lysette’s Antiques. The narrative primarily revolves around his final delivery, a shipment of antiques to Number 5, Dogwood Drive. The game starts and ends with that delivery, but Conway’s story doesn’t. His past and future unspool beyond the limits of the game — he’s just passing through.

An issue with his mission quickly becomes apparent: Dogwood Drive doesn’t seem to be a real place.

The only sure way to find an address that doesn’t exist, of course, is to travel by non-existent road, in this case, the liminal Route Zero. There are highways and back alleys and dirt tracks in this game — concrete, tangible routes that connect garages, TV repair shops and oddball roadside attractions. The Zero is none of these. The Zero is Kentucky’s collective memory of a road, an underground labyrinth of a forgotten Americana and forgotten Americans.

The Zero is recursive and nonsensical, something meant to be understood in the story as a narrative device as much as a real highway. The toll that travelling its length takes on Conway is very real.

One of the locations Conway visits along the Zero is the Hard Times whiskey distillery. He has racked up some debts at this point, having paid dearly in Act II to mend an injury to his leg. That leg becomes a potent visual reminder of those debts, of what his journey has taken from him, as, when he awakens after the surgery, his leg has been stripped of flesh, left skeletal.

The Hard Times Distillery is manned by others who have had the flesh stripped from their bones by hungry debtors. The distillery has purchased their debt, and the indebted will work it off there, forever. They’ll take Conway’s too, if he’s willing to sell it. Conway takes a drink in the Distillery, a shot of Hard Times’ signature whiskey, and like one of the lotus-eaters from The Odyssey, he never really leaves. The skeletal debt collectors from the distillery haunt him for the rest of the game, and eventually carry him out of the story altogether, down a dark tunnel to an end we never see.

Conway ultimately winds up as ineffectual and disempowered as the cat in Act V, as the Barfly, and as you, the player. He’s weakly pawing at his own history, looking back down the line at a story he can’t change, whose end seems inevitable. He can’t unmake himself; he will always struggle with alcoholism; he will always have driven his wife away.

This shell of a person was always waiting for him to become it.

Conway’s particular abjection — being a bystander to his own story, a passenger in his own life — is what I identified with in the lonely audienceship imposed on me by Kentucky Route Zero. Like a razor blade in a bag of candy, its resonance was wholly unexpected.

III

I feel very resentful of my younger self, sometimes, of the person who authored the first acts of my history.

Like Conway, I look back on the decisions I made, on the person I was, and I curse them. I was judgmental, eager to mock, insecure. I was nonbinary then, as I am now, but I hadn’t the words to voice my experience of being in concrete terms, to state it and speak it into reality.

I feel that the person I was before I defined and understood myself as I do now ran roughshod over my childhood, as though they stole from me the Act I that I could have — should have — lived differently. I can’t say I know what that would have looked like. Could I have been more at ease in my own skin? Less eager to put people down?

Better, prettier, kinder, wiser. What could I have been if I’d known better, sooner?

It’s worse not to know, I think, for that potential to remain forever unfulfilled. There’s a bitterness to feeling like player 2 in my own life, of having had to wait my turn to be myself, to have ceded so much time to a me-shaped someone that I don’t know how to feel about.

Do I wish I’d known that I was nonbinary years ago? Absolutely.

Do I wish I’d had that understanding, that control over my sense of self from a younger age? God yes.

It would have saved me confusion and embarrassment, but, in a way, that struggle is mine. It is me and I am it. I am an audience to my own history, but although I am apart from it now, isolated from that story, it is not apart from me — it is a part of me, etched onto my soul and scrawled on the inside of my skin. It’s in my eyes and in my throat, curling in my lungs like oily smoke.

That voyage of discovery informs me, contextualizes me, and as it turns out, I like me, now. If I hadn’t had to go on that difficult journey along my own Route Zero, maybe I’d be someone different, and I wouldn’t like me as much. I think it would be a shame if the me I am now — the messy, cobbled together version with a skeletal leg — didn’t get the chance to be thrown together slipshod from the bits and pieces I collected along the way. If Conway hadn’t been the damaged, kind man that his story had sculpted him into, would he have met the people he did? Would they have cared enough about him to see his delivery through?

IV

There’s a bit in Act IV of Kentucky Route Zero where a character called Will listens to his voice messages.

Will runs an automated phone line called Here and There Along the Echo, and people call in to that automated line and record early memories for him to listen to. Some messages are just a couple of lines, others minutes long, and Will listens to them all there, in the dark, by a phone booth along the Echo river. After he’s done, the helmsman of his tugboat, the Mucky Mammoth, asks him:

“Any important messages?”

“Every one,” he replies.

As invested in my own struggle for control over my life and my identity as I am, as important as it feels to me, I’m also one of those voice messages to most people. Less, even. I’m a figure on the bus, I’m “that’s a nice coat,” I’m “why are his nails painted?” Or I’m not noticed, a shadow.

I look around me, at the events of the last few years, and it’s impossible not to feel like I am passing through a story whose end extends beyond me. I’m barely hanging on by my fingernails while history careens through unprecedented event after unprecedented event like a bull in a china shop. Covid, Brexit, climate change fascism, genocide, racism, transphobia — it just feels like so, so much.

Like Conway, I’m trapped, suffocated by massive things beyond my control, but isn’t that true for all of us? Aren’t we trapped on the stage of history together?

We’re here under the scalding heat of the lights, and I for one cannot breathe for the speed and the fury of it. Seeing Conway borne away by those skeletal ferrymen, reduced to bones himself, is so powerful because it’s a fate I am scrambling to dodge. He’s denied the closure of finishing his quest, denied an ending. I do not want that. I dig in my heels and claw at the walls to avoid being dragged into the dark by circumstances beyond my control. I want to be remembered, to not be a footnote. I want my time to matter. I want to be more than the audience to a greater story, more than a reader of a story already told.

V

At the end of Kentucky Route Zero’s fifth act is a funeral.

The characters with whom we have travelled the Zero are there, but so are innumerable new faces, strangers both living and dead, and isn’t that so painfully honest? This is what we all are, in the grand scheme of things. We’re faces in a crowd, anonymous to one another. All, like Conway, just passing through not just one larger story, but millions. Billions. We’re all here, all important, all main characters in our own stories, indelible marks in the ledger of history, but tiny marks all the same; hastily sketched members of each other's audiences.

We’re writ large and small.

Alone, together.

There’s a beauty in that, I think. A beauty in being trapped in audienceship to each other.

History books crumble in the enormity of time, but we’ll always have been here. All of us. Time is huge and we’re so small, but we’re here, we’re here, we’re here. I’m here.

I’m not in control, not of the past, and not of the big picture — the closest I’ll get is when I’m a face at a protest, a name on a petition, but I’m here on my own personal journey along the Zero. We’re all, forever, the audience to history and to ourselves. The machinery of debt and merciless workings of the cultures we live in threaten to grind us up, to buy and sell us and strip us to our bones. But sometimes, for a while, we get to take hold of the controller, redefine ourselves, and fill in our sketchy outlines with new colour.