Remembering the Possiblities: ‘Katana Zero’ and The Collector’s Impulse

I fear that if I do not acquire a given thing, I cannot protect it from ceasing to exist as an artistic artifact.

There’s a false amnesia that can manifest when you’re swept up by the culture discourse vortex. That is, if you have many interests and uncertain priorities, it is easy to feel awash in responsibilities — what you want drives what you need, but how do you know what you want? Everyone has their hobbies, their scenes, and it’s easy to see flashes of things you can’t quite wrap your head around before they flash away into unreliable memories. Waves come and go, consensuses crest and break, attitudes around assessing art change. It is easy to feel like you are floundering in a sea of information if you cannot ground yourself in your values. I think memory and archiving are important, that we create ourselves through our interpretation of our experiences, and that how we share those experiences with others is important too. Regarding games, that once meant collecting discs in hopes of preserving the present as it fell into the past. In my case, being a player and a critic, that means trying to fill gaps in my gaming history, which leads to a constant resetting of expectations about what games are and what they can and should be. I am attempting to flesh out the snapshots gleaned from other people’s criticism and conversations with my own memories, the raw material of personal experience. The general gaming audience and the gaming press seem to value these things; the people who guide the industry seem ambivalent and sometimes hostile toward them.

When critically discussing film, games, television, and literature, I’m always concerned that I’m not knowledgeable enough, that I am not collecting enough input to output useful insights, as if I’m a machine low on fuel because I can’t decide what octane is best for my engine. Have I engaged with the medium (any medium) sufficiently to have anything worthwhile to say? Why am I always catching up? How do I become “current?” This creates an impulse or compulsion to collect more inputs, which itself is perpetuated by being born and raised in a consumerist society that renders things disposable to the extent that I fear if I do not acquire a given thing, I cannot protect it from ceasing to exist as an artistic artifact.

If I recall correctly — which I may not — I purchased my PlayStation 3 and my Xbox Series X about eight years apart, early 2013 and early 2021 respectively, both by way of tax refunds. I got the PS3 just months before the PS4 was released in the hopes of backfilling my gaming memory, filling in knowledge of the near-decade of games I had heard or read about but had missed while playing NCAA Football on my PS2. I was simultaneously playing both adult and child in a now decades-old Katt Williams standup bit. I continued to play NCAA Football ’06 and ’07 on the fourth PS2 I was whole or partial owner of and then NCAA Football ’11 and ’14 (the last version of the game before a decade-long hiatus) on my PS3, but my PS3 was primarily dedicated to narrative games. That was where, in 2013 and 2014, I played all three Mass Effect games, BioShock: Infinite, Saint’s Row III, Far Cry 3, Fallout 3 and New Vegas, and Batman: Arkham Origins.

During the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, the soul-searching of the summer led me to reflect on the assortment of half-finished and untouched games amassed from GameStop bargain shelves and impulsive eBay searches. Purchased to fill gaps in my understanding and discarded for different experiments in fictional college football program building, they found new life in that endless summer. I replayed Grand Theft Auto V, unlocked both endings of GTA IV, and beat the first two Batman: Arkham games in 2020 and 2021. I thought I didn’t like Skyrim much, but I revisited my last save file recently and saw I put nearly 100 hours into it during the same years. This number may not sound lofty for a fan of the series, but it was a lot for someone who thought the game was just “fine.”

Part of what enticed me to the Series X instead of the PS5 — setting aside the fact that they were both affected by global supply chain shortages, meaning I likely purchased whichever one was more readily available — was the Series X’s backward compatibility stretching back to the original Xbox and the subscription service Game Pass, both of which gave me access to a vast library of games I had heard of but hadn’t played. There is an infinite backlog and a tremendous canon, and I felt I could restart my relationship to games with access to both the new and the old. Almost everything that ever came out on the first three Xbox consoles, plus some of things gradually ported over, were new to me. As enticing as it was, this model seems to have struggled to bring in the returns on investment that Microsoft and the developers involved had hoped. The mixed results are symptomatic of irrational financial thinking which increasingly guides related media and tech industries, an ethos committed to consolidation based on a hypothesis of infinite growth where setbacks are often treated as unforeseeable surprises.

There are too many games for anyone to play all of them. HowLongToBeat has 72,300 games recorded, Geeky Matters recorded 831,000 “across all accessible platforms” in December of 2023, and WebTribunal recorded 831,523 in May of 2023. If they all took exactly one minute to play and you had no other responsibilities including eating, hydrating, disposing of associated waste, or otherwise working, it would take 577.45 days to play them all. Most take considerably longer than one minute to play — HowLongToBeat has the median game playtime at 18 hours and 7 minutes. Meanwhile, the Video Game History foundation finds that 87% of classic video games are not readily available by legal means. Dune 2000, my first foray into RTS games, isn’t on Steam or GOG but can be found in the legal gray area of free online hosting for abandonware.

I spent my early Xbox days cruising Game Pass, trying to download as many small indie games as the 1TB hard drive could fit. One of the titles I played was Katana Zero, a 2019 indie game ported over to the Series X that I purchased after it came off the service. I’m sure I heard of it before I bought the Xbox, but it was one of the first games recommended by a friend when I asked what I should play on the console. Putting “katana” in a title is likely to draw my attention regardless of quality, but the screenshots and videos depicting side scrolling action platforming grabbed me tightly, and playing out that action held me close. “Quick combat with a cerebral strategic element set against an urban samurai aesthetic in a dystopian urban setting” is a safe pitch for me.

Designed and programmed by Justin Stander, written by Stander and Eric Shumaker, and published by Devolver Digital, Katana Zero is a bloody violent game about trauma, clairvoyance, and cutting people up set to a delectable soundtrack (from Stander, LudoWic, Bill Kiley, DJ Electrohead, and Tunç Çakir) that alternates between electronic music during combat and pretty pianos in cutscenes. In the Hotline Miami style, any single hit can kill you, so the action revolves around avoiding attacks using jumps and rolls while parrying bullets with a narrative-defining bullet-time mechanic to cut them down before they can react.

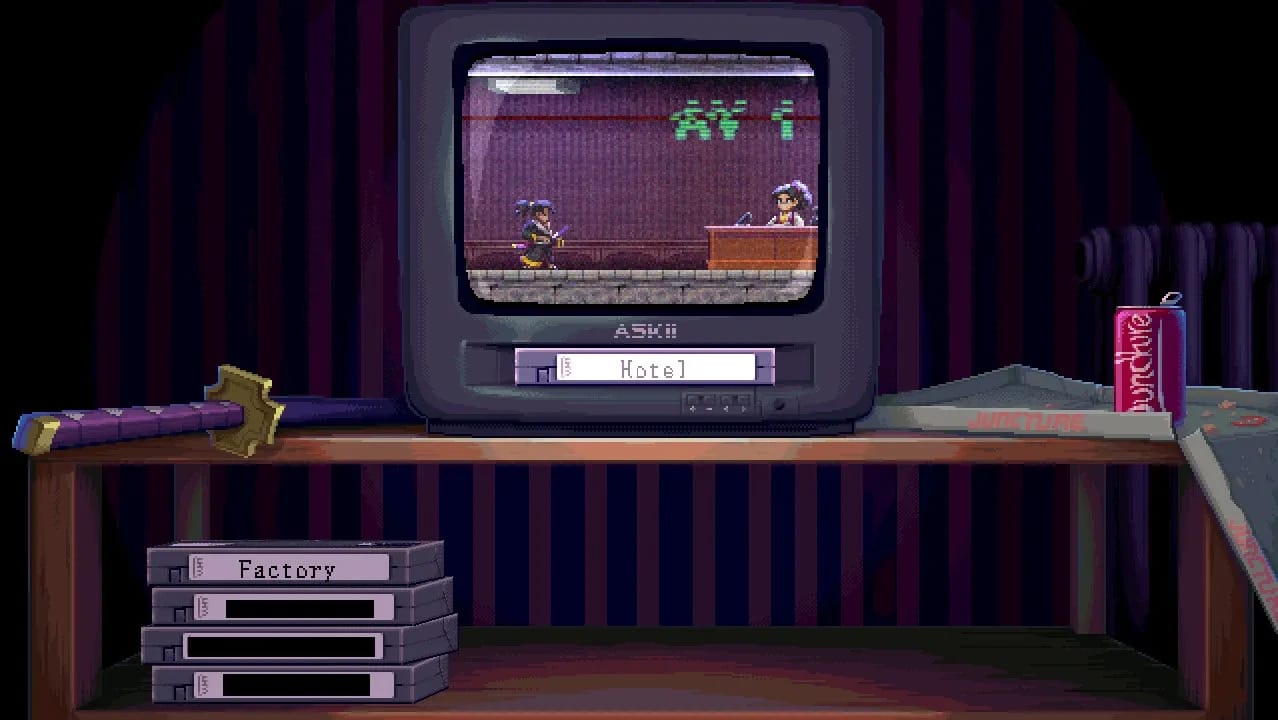

Katana Zero’s aesthetic is decidedly retro, drawing a detailed pixel art world with clear reference to pioneering cyberpunk works like Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell, as the swordsman Zero lives in a dreary, often raining, dystopian metropolis. Initially, I assume the outfit is standard in the setting, but then our swordsman protagonist is mistaken for an anime convention cosplayer and referred to by police as wearing a “bathrobe.” The identity he has constructed to deal with his war-induced PTSD isolates him from society. He’s given assassination assignments in manila folders labeled “Destroy After Reading” from a psychiatrist helping him deal with his mental problems, and he is haunted by disturbing dreams from military service. The case manager ends their sessions in an abrupt and placating fashion, administering “Chronos,” the drug that gives the protagonist clairvoyance and super-agility, which manifest as the game’s bullet-time mechanic and death-invoked mission restart. He is facilitating a dependence from which there is no escape. After every death, a caption appears saying “No, that won’t work.” With each reset, the protagonist accrues memories of possibilities, of futures that never come to pass, as he hypothesizes different resolutions for each combat sequence. After each part of the level, you view a black-and-white replay of the sequence recorded by security cameras; if you execute it well, it looks very cool and adds to the action movie vibe. When you eventually unlock stage selection, each level is displayed as a security tape in a stack in front of a television. It is the capture of your experience through technology, to be revisited — or dropped out of — at your leisure.

I have never been a speedrunner. I tend to take my time, even too much time, with games. Does that mean the games are not interesting enough to hold my attention, or am I just too flighty? No one wants their 40 hours wasted, but you have to agree to invest time if you want to form a clear opinion about an experience. Separating yourself out from that experience, intentionally or incidentally, requires a reset of some sort — do you pick up where you left off or restart entirely to relearn the mechanics and get your head back around the narrative? Sometimes I lose focus (I took time off Mass Effect 3 to play NCAA’s dynasty mode), sometimes I lose patience (I took time off BioShock: Infinite because of a bad boss fight), and sometimes I get bored. Recently, I have just wanted to dabble across genres and sit still in their worlds. There’s that tension between having a breadth and depth of experiences to draw on when developing your tastes and bringing them to bear on how you engage with a medium. In any case, doesn’t rushing through run the risk of diminishing the experience?

Gaming criticism and culture take care to remember old games and indie darlings like Katana Zero. Conversely, the game industry runs on short memories, often opting to restart from ground zero. From a marketing standpoint, limiting the public’s knowledge of industry’s history is helpful when it comes to reselling old ideas either as remakes or, increasingly, as licenses rather than products. For developers, the perpetual bloodletting in the form of mass layoffs has the side effect of reducing institutional memory and therefore undermining development of the art form. The expansion of budgets often undercuts artistic ambitions, and the need for the revenue line to always go up means that even a small setback leads to merciless cost cutting. (Generously speaking, this is less of a consequence of the ambitions and whims of developers themselves and more a result of private equity in non–publicly traded companies or venture capital in publicly traded ventures.)

This cold calculation means that the people who control the industry are not the most emotionally nor philosophically invested in preserving or developing the art form. They don’t care to archive the past. We might not be restarting from square one, but we’re certainly losing some core memories along the way. And, as much as it is a result of the guiding ethos of the capital class, it is also the result of game directors-turned-CEOs like Ken Levine having oversized egos and minimal project management skills and programmers-turned-CEOs like Phil Spencer piloting the purchase of dozens of development studios and one $69 billion acquisition, only to close several of these studios after both failures and award-winning successes. Games is a hostile industry to work in because of the loudest, least-informed audience members, and ever more tenuous and fraught labor conditions. The media that covers this industry is similarly unstable, subject to the same financial burdens. Tied as the medium is to the tech industry and youth culture, the recent past can frequently feel ancient. What’s not yet gone is nonetheless easily and frequently forgotten, an enforced amnesia from the industry’s stakeholders. There’s no real restart for these bad decisions, no Chronos and no preemptive strategy.

In trying to assemble my own memory of games as medium and industry, I find myself taking shallow sips from different cups at the medium’s table. I dabble here and there, getting sucked in and lost in games, reading contemporary reviews and older reviews and listening to four-hour podcast episodes about why Mass Effect 3 sucks. I feel called to acquire games (and books and movies) although I sometimes struggle to make time before, as with Spec-Ops: The Line earlier this year, they get suddenly delisted and go from being a $10 Microsoft Store purchase to costing hundreds of dollars on eBay.

The goal in my quest here has little in common with Zero’s except that I feel like I am rebuilding a memory, coloring in an outline, perhaps more conscious of the fabrication involved than Katana Zero’s protagonist. The stakes of the truths we seek are disparate and the people I seek help from aren’t obfuscating reality to use me to their own ends. I am seeking understanding and contributing to the understanding of art forms, trying to learn about what I love so I can communicate that love, explain the value I invest in the medium. Maybe I’ve got a longer time limit, but I can’t see the future. I’m simply working, with lots of help and challenges, to see the past.